In today’s fast-evolving financial landscape, what counts as normal is increasingly hard to define. Markets drift into regimes where traditional signposts—like historical averages or steady policy anchors—no longer map neatly onto outcomes. This article delves into why the line between normal and abnormal appears blurred, pulling from a set of indicators, debt dynamics, policy shifts, and the accelerating impact of inflation on price discovery. It maps how traders and investors might interpret these signals in a world where the once-reliable relationships between rates, growth, and asset prices no longer hold in the same way they did a decade ago. The purpose is not to predict with certainty but to illuminate how a probabilistic, data-driven approach can help navigate a market that feels perpetually out of balance.

Reframing Normal and Abnormal in Modern Markets

Normal, in classical economics, centered on stable statistical relationships. We relied on averages, standard deviations, and probability theory to gauge what was likely to occur and what fell outside expected ranges. This framework allowed practitioners to set expectations, price risk, and anticipate regimes where valuations might revert to historical norms. The modern era challenges that framework in multiple, compounding ways. The global economy has entered a phase where inflation remains stubborn and perceptions of value are distorted by unprecedented monetary and fiscal interventions. In such a context, distinguishing normal from abnormal requires a nuanced synthesis of quantitative metrics and qualitative signals, recognizing that the past is no longer a precise forecast for the future.

This article explores a line of evidence suggesting that current economic and market conditions depart significantly from traditional norms. A central theme is permanent inflation—a regime in which price levels tend to stay elevated and reduction towards prior baselines becomes increasingly difficult. For traders and investors, this shifts the risk-reward calculus in ways that traditional models struggle to capture. The analytical approach proposed here emphasizes asking meaningful questions, using probabilistic reasoning, and interpreting charts through the lens of long-run historical context. The objective is to develop a framework that helps practitioners adapt to evolving market dynamics rather than clinging to outdated assumptions about where normal ought to reside.

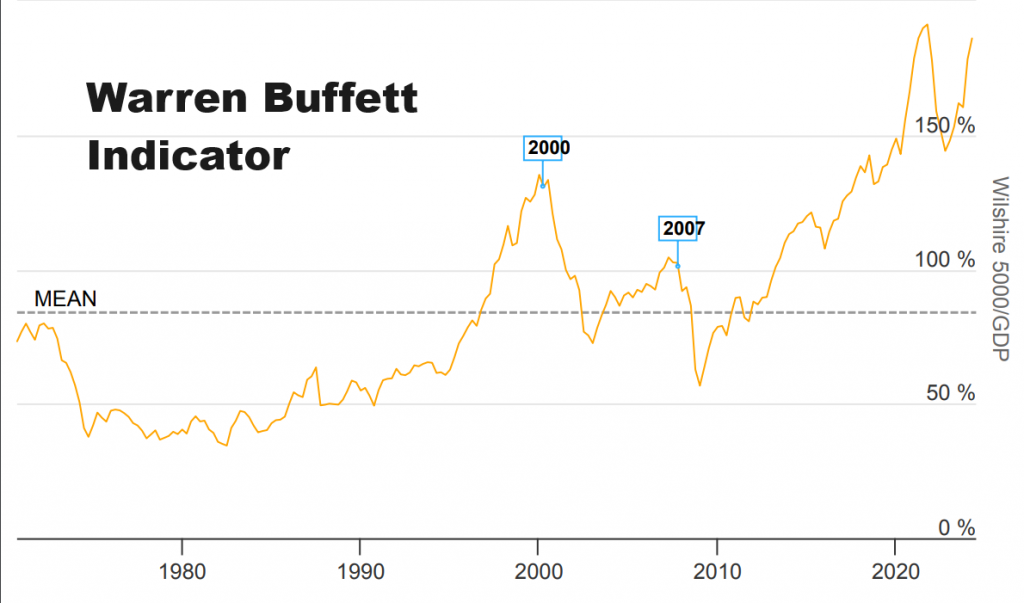

To begin, it is useful to anchor the discussion with a well-known yardstick in market analysis: the Warren Buffett Indicator. This metric compares the total market capitalization of a country’s equity market to its GDP. Historically, this ratio has helped define normal and abnormal market environments by signaling overvaluation when the ratio rises far above 100 percent and undervaluation when it sits below that benchmark. By tracking deviations from historical averages, investors could gauge whether the market was in bubble territory or undervalued relative to the country’s economic output, informing investment decisions accordingly. That historical utility remains relevant, but current readings are pushing the boundaries of what was once considered normal.

The Warren Buffett Indicator today sits at a level around 193 percent, a striking elevation that is approaching new all-time highs. This extreme value suggests that the stock market’s total valuation dwarfs the nation’s GDP, indicating overvaluation on a historical basis and increasing risk of a market bubble. In prior cycles, such extreme readings have preceded meaningful corrections, declines, or even downturns as the market reverts toward long-run relationships between asset prices and economic activity. The present configuration of this indicator strengthens the argument that the current environment may be categorized as abnormal relative to long-run norms. It is a powerful reminder that overvaluation signals, when taken in the context of broader macro forces, merit careful attention.

When examining the historical mean of the Buffett Indicator over a 60-year window, the mean runs close to 80 percent. That long-run average provides a baseline against which to judge current conditions. From this vantage point, the last time the indicator reached levels as elevated as today was in November 2021. At that time, several macro elements aligned in ways that reinforced a perception of overvaluation, including the Federal Funds Rate remaining in the target range of 0.00 percent to 0.25 percent—a policy stance designed to support economic recovery during the COVID-19 pandemic. By contrast, as of June 2024, the Federal Funds Rate sits at 5.33 percent, marking a dramatic shift in monetary policy stance over a relatively short horizon.

These observations lead to a provocative question: how can rates rise by more than a factor since late 2021 while the stock market continues to rise or at least hold above previous levels? The traditional macroeconomic adage—“when interest rates are high, stocks will suffer; when rates are low, stocks will rally”—has historically explained much of the direction of equity markets. But the current environment complicates that narrative. The period from November 2021 to June 2024 demonstrates that high interest rates did not uniformly translate into a collapsing stock market, prompting a reassessment of the causal links between financing costs and equity valuations. The broader implication for traders is clear: the relationship between rates and equities remains a critical lens, but it no longer functions as a simple rule of thumb in a regime shaped by persistent inflation expectations, unique fiscal dynamics, and evolving financial-market structure.

This redefinition of normal is not merely academic. It affects how traders gauge risk, allocate capital, and interpret price action in an environment where the historical anchors may be less reliable. The argument advanced here is that the era of “Permanent Inflation” changes the calculus of asset pricing, debt sustainability, and policy transmission, requiring a broader toolkit and a willingness to adapt strategies to evolving conditions. The rest of this analysis unpacks several interconnected pillars that together sketch a picture of an abnormal financial regime and what it means for those who trade within it.

The Warren Buffett Indicator: Current Readings, History, and Implications

The Warren Buffett Indicator has long served as a straightforward barometer of market valuation relative to the size of the economy. It is calculated by dividing the total market capitalization of a country’s stock market by its gross domestic product (GDP). When the ratio sits near or below 100 percent, the market has historically been construed as fairly valued to modestly undervalued relative to GDP. When the ratio climbs significantly above 100 percent, investors have tended to view the market as overvalued, with heightened risk of a price correction or downturn if earnings growth cannot keep pace with the expansion in market value.

Over the past several decades, this indicator has proven useful because it condenses a great deal of information into a single, interpretable figure: the relationship between equity market value and the underlying economy’s productive capacity. It is not a precise forecast tool, but it provides a meaningful perspective on whether the market has detached from the economy’s real size. Investors and analysts have used the ratio to calibrate expectations about future returns, risk of bubbles, and the potential for mean reversion in valuations.

Today, the indicator stands at approximately 193 percent, signaling a level of overvaluation that exceeds historical norms and is approaching an all-time high. From a historical standpoint, such a reading is a cautionary flag: valuations are elevated relative to GDP in a way that historically coincides with periods of elevated risk or, in some cycles, impending corrections. The indicator’s trajectory invites a careful assessment of the probability-weighted outcomes for equities given a backdrop of inflated multiples and uncertain earnings trajectories.

Notably, the mean of the Buffett Indicator over a 60-year horizon is around 80 percent, underscoring the magnitude of the current divergence from deep historical norms. The last time the ratio was this elevated was November 2021, a period in which the Federal Funds Rate sat at 0.00–0.25 percent and monetary policy was anchored in crisis-era ease to support COVID-era recovery. Comparing that moment to today reveals a stark policy shift: the Fed has since increased rates to a target of 5.33 percent, constructing a different environment for corporate profitability, debt servicing, and equity valuations.

Amid these changes, the question persists: what does a 193 percent Buffett Indicator imply for investment decisions in the near to mid-term? The interpretation hinges on multiple factors. First, the indicator signals that the stock market’s overall value is high relative to the economy’s size, suggesting elevated risk of a correction if earnings growth slows or if inflation expectations intensify further. Second, it underscores the potential for a regime where multiples may compress or where returns are driven more by earnings resilience than by price growth alone. Third, it emphasizes the importance of diversification and risk controls, given that markets can remain overvalued for extended periods before a meaningful reversion occurs, especially in a milieu of policy-induced liquidity shifts and structural changes in interest rates.

In addition to the numerical reading, traders should consider the broader macro backdrop. A high Buffett Indicator often coincides with inflation pressures, policy uncertainty, and shifts in capital formation. The current configuration suggests that investors are pricing in robust future earnings or exceptional monetization of growth strategies, even as macroeconomic headwinds—such as persistent inflation, higher borrowing costs, and the evolving fiscal stance—pose potential risks to the durability of equity profits. The composite signal is not a call to abandon equities but a reminder to moderate expectations, calibrate risk budgets, and emphasize high-quality earnings, resilient balance sheets, and defensible competitive moats in portfolio construction.

The implications for asset allocation are nuanced. On one hand, a high Buffett Indicator could imply a tighter risk budget for equity exposure, particularly for speculative or cyclically sensitive segments. On the other hand, equities may still deliver favorable absolute returns if earnings trajectories and demand conditions prove more resilient than anticipated, or if monetary policy eases in response to softer inflation dynamics without derailing growth. The key for traders is to monitor a spectrum of signals—valuation, macro data, earnings quality, and policy expectations—in order to navigate a regime where traditional valuation anchors are stretched but not entirely invalid. In sum, the Buffett Indicator remains a meaningful compass for long-run valuation context, but its readings in the current epoch demand careful interpretation within a holistic framework that accounts for the peculiarities of Permanent Inflation, debt dynamics, and the evolving policy environment.

The Paradox of High Rates and a Rising Market: What Is Driving the Anomaly?

Conventional macroeconomic doctrine offers a straightforward intuition: higher interest rates raise the cost of capital, dampen investment, and weigh on stock prices; conversely, lower rates reduce borrowing costs, stimulate investment, and tend to buoy equity valuations. This intuitive framework has guided investors for generations, and it generally holds across business cycles. Yet the current period presents a paradox: interest rates are markedly higher than they were in late 2021, while stock indices have not collapsed in line with the old rulebook. In November 2021, the Federal Funds Rate rested in the zero-to-low territory, and a consistent policy push supported economic recovery after the initial pandemic shock. By mid-2024, the policy stance had shifted to a 5.33 percent target, reflecting an aggressive attempt to tamp down inflation and rebalance demand. Against that backdrop, it is not obvious why the stock market would sustain, let alone advance, relative to the level implied by a simple rate-equals-price dynamic.

One way to approach this puzzle is to recall the historical relationship between rates and equity valuations as a probabilistic relationship rather than a deterministic one. There are periods where higher rates coincide with rising stock prices because other factors—such as strong earnings growth, innovative technologies, or macroeconomic tailwinds—offset the headwinds from financing costs. The current environment is a confluence of several powerful drivers: persistent inflation expectations that sustain nominal demand resilience, a large structural shift in savings and investment behavior, and a multi-year policy framework that has kept liquidity support in the system in nuanced ways even as policy rates rise. The paradox arises when one uses a single-variable lens to explain a multifaceted system; a more robust view considers how real rates, inflation risk premiums, and expectations for future policy paths interact with corporate profitability, productivity gains, and demand strength.

To illustrate the tension, consider how high rates influence corporate decisions. Higher rates raise debt-servicing costs, compress margins for firms with heavy leverage, and can slow capital expenditure. They can also heighten the hurdle rate for investment projects, curtail share repurchases in some segments, and tilt preference toward companies with robust cash flows and strong balance sheets. Yet, if the macro environment includes confident consumer demand, resilience in employment, and structural shifts toward digitalization or AI-driven productivity, then equities can maintain valued levels and even extend gains despite the higher rate regime. This dynamic does not negate risk; instead, it reframes risk: the market may be pricing in higher discount rates and more uncertain growth trajectories, which could compress future returns if the inflation picture deteriorates or if growth slows more than expected.

From a trader’s perspective, the key takeaway is to avoid overreliance on a single indicator or a single narrative. Rates matter, but so do the sources of earnings, the sectoral composition of the market, the institution of risk controls, and the ability of the market to digest ongoing policy shifts. In an era of Permanent Inflation, inflation expectations themselves can become a source of stability or instability, depending on how credible the central bank’s response proves to be and how fiscal dynamics align with the currency’s value. The paradox of a high-rate environment coexisting with a rising market is not a sign of complete rationality but rather a signal of a market in a regime where multiple forces interact in non-linear ways. Traders who can parse these interactions—while maintaining disciplined risk management and diversified exposure—may be better positioned to navigate the turbulence and identify pockets where value, earnings resilience, and strategic positioning align with forward-looking risks.

The broader implication for investors is that traditional single-factor heuristics are insufficient in the present regime. A holistic framework that blends valuation metrics, rate expectations, inflation trajectories, and the health of the credit environment is necessary. Such an approach helps distinguish temporary dislocations from regime shifts and informs decisions about hedging, liquidity management, and tactical allocation. In the pages ahead, we examine additional threads that feed into the current abnormal state of the macro-financial system, including the trajectory of debt, the health of the banking sector, and the policy options available to finance a growing bill of obligations.

The National Debt, Interest Payments, and the Financing Challenge Ahead

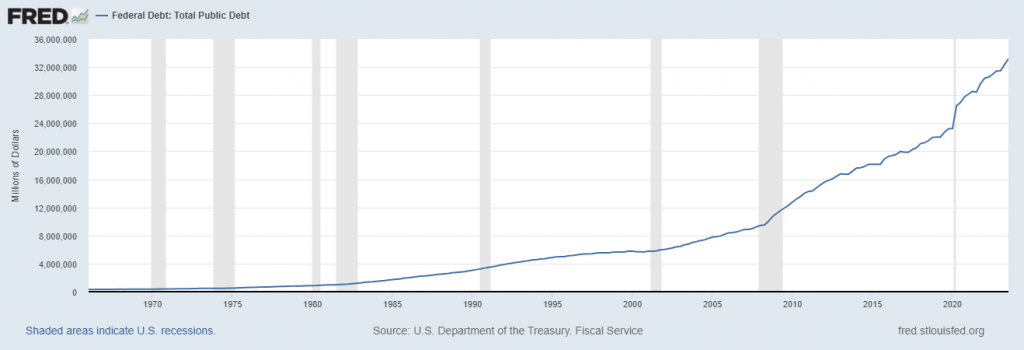

A central source of concern in the present environment is the growth of interest payments on the national debt and the consequent pressure this places on government budgets. In a striking development, interest payments on U.S. debt recently crossed the $1 trillion threshold, surpassing the domestic portion of military spending within the federal budget. This milestone translates, in part, to a dramatic rise from November 2021, when interest payments were approximately $600 billion. In less than three years, the debt-service bill has grown by about 66 percent, underscoring the way in which financing costs have surged as debt levels and rates have risen.

The budgeting landscape is dominated in the near term by social programs, with Social Security consuming roughly $1.3 trillion in annual outlays. If current trajectories persist, interest payments on the debt are projected to surpass Social Security spending within roughly 18 months. The rapid growth of debt-service costs raises hard questions about sustainability and the choices the government faces to fund operations, meet obligations, and maintain the credibility of Treasury securities in a crowded and sometimes fragile market.

A key, often overlooked, question centers on who will purchase the debt that must be rolled or refinanced. In recent years, Treasury auctions have shown stable demand for short-to-medium-term maturities, with buyers continuing to participate in the near term. However, demand for longer-dated securities appears tempered, suggesting a crowding-out of long-duration debt as investors seek liquidity and lower duration risk in an inflationary environment. The difficulty extends beyond market appetite to technical constraints: the reliability of the debt-management framework depends on a stable demand base and the ability to attract buyers even as the supply of new securities expands with ongoing deficits.

From a structural perspective, the question of funding the government over the next several years is inextricably linked to the broader monetary policy and the actions (and inactions) of the Federal Reserve. One line of reasoning holds that the Fed’s willingness to purchase Treasuries serves a critical function in stabilizing funding conditions and ensuring that the government can finance the deficit at manageable rates. If the central bank withdraws this support, markets could face sharper adjustments, particularly if inflation and the inflation premium remain persistent. Conversely, if theFed maintains a restrictive stance without adequate demand for debt, the government could confront higher borrowing costs and greater the fiscal deterioration, magnifying downside risks to both the currency and bond markets.

Traders and policymakers are watching a simple-but-crucial metric: the total refinancing need over the coming years. A rough calculation suggests that about $7.6 trillion of U.S. government debt matures in the next year, representing roughly 31 percent of the total outstanding debt. Projection over three years implies that the annual refinancing needs could triple, assuming the pattern of maturing debt remains relatively constant. A conservative estimate for refinancing needs over the next four years sits around $22.8 trillion, acknowledging that such an estimate abstracts from any major shifts in fiscal policy or unexpected changes in borrowing requirements. The implications are straightforward: as the number of maturities grows, the demand for buyers—whether domestic or foreign, private or public—becomes more critical, and the market’s tolerance for continued deficits becomes a central determinant of the path of interest rates, inflation expectations, and the risk premia embedded in Treasuries.

The interplay between debt refinancing and monetary policy has important consequences for the broader economy. If the Federal Reserve chooses to continue purchases of Treasuries to support the markets, this would help keep financing costs in check and prevent a sudden tightening that could derail growth. However, such purchases also raise the threat of persistent monetization of the deficit, raising concerns about the reacceleration of inflation in the medium term and fuel the argument for a more sustained inflation regime. If the Fed withdraws support, or if the market loses faith in the government’s ability to manage deficits, the risk of a sharp rise in long-term rates could intensify, potentially triggering higher debt-service costs for a broad set of borrowers and creating spillovers into housing, corporate credit, and consumer financing.

There is also a broader, more philosophical question about debt sustainability in a post-crisis economic order. How long can the government sustain debt expansion while still preserving the credibility of Treasuries and the currency’s reserve status? The answer will hinge on a combination of policy choices, external financing conditions, and market discipline. The current reality—an acceleration of debt beyond pre-pandemic levels and a debt-service burden that has eclipsed a major line item in the budget—signals that the financing regime will remain a central, ongoing topic for investors and policymakers alike. As the nation moves through the next few years, debt dynamics will continue to shape the incentive structures for investment, savings, and consumption, with potential implications for inflation, currency value, and financial stability. The interplay between debt, inflation, and policy will influence risk appetite, asset pricing, and the durability of the U.S. financial system in a shifting global landscape.

Banking Sector Health in an Uneasy Economic Environment

A robust banking sector is a linchpin of a healthy economy. Banks support lending to businesses and households, provide liquidity, and facilitate capital formation. The health of the banking system, however, is not a standalone metric; it is profoundly influenced by the overall economic environment, including growth prospects, inflation, interest rates, and credit quality. A disturbing pattern has emerged in recent observations: the realized gains and losses on the books of U.S. banks, as reported by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), have drawn attention to the composition and risk profile of bank balance sheets. The standout feature in these observations is the sizable exposure to U.S. Treasuries as assets on bank books. In many cases, Treasuries constitute the largest, or one of the largest, security holdings for banks. The question this raises is straightforward: how can the banking system appear more fragile from a solvency perspective today than it did during the 2008 financial crisis, even as monetary authorities claim that the economy remains resilient and robust?

To understand the concern, it is essential to reflect on the relationships among economic health, bank solvency, and asset quality. Banks depend on a broad ecosystem of borrowers and depositors. When the economy is strong, borrowers tend to expand their activities, leading to higher loan demand, better repayment performance, and stronger fee revenue from services. The resulting uplift in earnings supports capital and asset quality. Conversely, during periods of economic stress, default losses can rise, earnings shrink, and banks may encounter funding pressures as the outlook for credit quality darkens. The health of the banking sector often serves as a barometer of the broader economy because banks are, in effect, financial intermediaries bridging saving, investment, and consumption.

The FDIC data revealing strong exposure to Treasuries points to a structural dynamic within the sector: the search for liquidity and safety in an environment of uncertain inflation and policy shifts. While Treasuries are highly liquid and historically considered safe assets, the concentration of these holdings can present concentration risk if inflation remains persistent or if rates move dramatically. If investors suddenly demand higher yields or a reevaluation of risk occurs, banks’ interest-rate risk and the mark-to-market value of these holdings could shift more abruptly than anticipated. In such an environment, even when the macro narrative suggests resilience, underlying solvency metrics can reveal vulnerabilities that warrant scrutiny. The juxtaposition of these signals—robust financial institutions in some dimensions and rising concerns about balance sheet durability in others—underscores the complexity of assessing overall financial stability.

Traders and policymakers must also consider how the health of banks interplays with consumer credit conditions, investment appetite, and the stability of the payments system. An economy with healthier banks tends to support more robust lending, which can sustain growth and uplift asset prices. However, if credit conditions tighten as a response to higher rates and inflation, demand for loans could slow, potentially influencing economic activity and market sentiment. It is precisely this duality—the potential for apparent strength in banking metrics to coexist with emerging cracks in credit quality—that makes the current environment particularly challenging to navigate. The takeaway for market participants is to monitor the quality of loan portfolios, the sensitivity of bank earnings to interest-rate shifts, and the liquidity dynamics of the broader financial system, as these elements collectively shape risk premia, capital adequacy, and the resilience of the banking sector in the face of persistent inflation and rising deficits.

The overarching narrative is a cautionary one: the health of the banking system is vital, but not a standalone positive signal if paired with structural challenges in debt sustainability, inflation persistence, and political risk. The balancing act for traders consists of recognizing that the financial system’s stability depends on a complex set of interdependent variables, including Treasuries’ role as the backbone of domestic finance, the behavior of non-bank lenders, and the demand for safe assets amid a sea of uncertainty. In a world where the health of banks and the strength of the economy are not perfectly aligned, risk management becomes essential. Traders should ensure that liquidity is preserved, hedges are in place for adverse scenarios, and that portfolio construction accounts for potential shifts in consumer credit and capital flows that can ripple through markets in unforeseen ways.

In sum, the banking sector’s health in the current regime is a nuanced mosaic. It reflects resilience in some dimensions—such as the continued ability of banks to operate as intermediaries—and concern in others, particularly the sensitivity of balance sheets to interest-rate movements and the heavy concentration in Treasuries. Those assessing financial stability must weigh the evidence across multiple indicators, including debt dynamics, policy settings, and market demand for housing, credit, and investment. The reality remains that a robust, well-capitalized banking system is necessary but not sufficient to guarantee macroeconomic stability in the face of the Permanent Inflation regime and the evolving fiscal landscape.

The Unrealized-Capital-Gains Tax Debate and Its Market Consequences

A striking feature of recent policy discussions is the consideration of a tax on unrealized capital gains—essentially a levy on profits that have not yet been realized through a sale. In a conventional framework, taxes are assessed at the point of sale, based on the transaction’s gain or loss. In a world where policymakers contemplate taxing unrealized gains, the incentives for investors to hold assets or exit positions could shift dramatically, with profound implications for market dynamics.

If unrealized gains were taxed currently, the immediate effect would likely be heightened market volatility. Investors might be forced to realize gains or to sell assets to cover tax liabilities, irrespective of whether those gains had actually crystallized in cash through a sale. Such a policy could provoke a wave of forced liquidations across a broad spectrum of asset classes, including equities, bonds, and real estate. The resulting oversupply of assets on the market could depress prices and create a feedback loop of lower valuations and higher tax obligations, potentially amplifying market stress during periods of elevated uncertainty.

The political logic behind unrealized gains taxation can be framed as a response to long-standing fiscal pressures and perceived gaps between revenue needs and budget commitments. In the view of proponents, such a policy could enhance government solvency and align tax receipts with the true value of asset price movements, even if those gains surpass the level of cash realized in a given period. Critics, however, warn that the policy could erode investment incentives, discourage risk-taking, and destabilize financial markets during a period of structural inflation and high debt service.

From a trader’s perspective, the prospect of unrealized gains taxation introduces a new regime of risk assessment and asset-liability management. Market participants would need to model not only price trajectories and cash-flow yields but also the tax timing implications of various strategies. Portfolio rebalancing would become more complex as investors weigh after-tax outcomes alongside pre-tax profitability. The potential for sudden tax-triggered liquidity events would raise the importance of liquidity reserves, risk controls, and hedging, particularly for leveraged positions and assets with sizable unrealized gains.

Despite its potential to alter market dynamics, unrealized gains taxation remains a controversial and debated policy instrument. Its adoption would depend on broader political negotiations, macroeconomic conditions, and the credibility of tax administration. Nevertheless, the discussion itself signals a broader trait of the current era: policymakers contemplating structural reforms to address debt dynamics are willing to consider radical departures from established tax norms. For traders, staying attuned to these policy debates and understanding their possible implications for asset pricing and liquidity is critical in navigating the evolving terrain.

In the broader scheme, unrealized capital gains taxation is emblematic of heightened fiscal pressure and the willingness of policymakers to explore unconventional tools in pursuit of balance sheet repair. It underscores the reality that the market environment is not static and that policy decisions can unpredictably alter incentives, risk premia, and market liquidity. Traders should therefore maintain flexible strategies, stress-test for various policy outcomes, and prioritize risk management practices that can withstand unexpected shifts in tax policy or policy signaling.

Permanent Inflation: Currency Debasement, Purchasing Power, and Market Implications

Since the advent of the modern monetary regime, the U.S. dollar has experienced a long arc of depreciation in purchasing power, a trend that has accelerated in the wake of expansive monetary policy and sustained deficits. The notion of Permanent Inflation captures the intuition that price levels in major economies may settle at higher average levels than seen in previous decades, creating a new normal in which currency grants less real purchasing power over time. This framework has sweeping implications for savers, investors, and policymakers alike.

A core concern is the ongoing debasement of the currency and its impact on real returns. If inflation remains persistent, nominal gains in asset prices may be offset by erosion in purchasing power, leading to scenarios where even seemingly positive returns translate into negative real returns after inflation adjustments. This dynamic can foster a reevaluation of asset-class attractiveness, with greater emphasis placed on inflation-hedging investments, such as real assets, and on strategies designed to preserve or grow purchasing power in a high-inflation regime.

Where does Permanent Inflation originate? A complex mix of policy choices, global supply constraints, and near-term demand dynamics can contribute to a durable inflation regime. The combination of substantial government spending, rising debt-service costs, and the central bank’s response to inflation expectations can generate a self-reinforcing cycle in which prices adjust higher, expectations become anchored at elevated levels, and policy actions aim to cap demand without triggering a sharper recession. In such an environment, it becomes harder for the economy—and for ordinary households—to return to the pre-crisis baseline of inflation that dominated the first decade of this century.

The market implications of Permanent Inflation are multifaceted. For one, discount rates used in asset pricing tend to incorporate higher expected inflation risk, which can compress real returns across a broad spectrum of investments unless compensated by risk premia or growth surprises. Equities may still offer upside due to earnings growth and productivity gains, but the valuation multiples may face pressure from persistent inflation expectations, rising financing costs, and uncertain policy signals. Fixed income instruments, particularly longer-duration Treasuries, may see heightened sensitivity to rate changes and inflation surprises, influencing the relative attractiveness of bonds versus equities. In this context, a diversified approach that balances inflation-sensitive assets with quality equities and options-based hedges can help manage risks associated with inflation persistence.

From a trader’s viewpoint, assessing risk in a Permanent Inflation regime requires a focus on pricing power, balance-sheet resilience, and the sensitivity of cash flows to rising prices. Companies with pricing power and durable competitive advantages may fare better in such an environment, while those with high leverage or sensitive cost structures may struggle as financing costs escalate. The macro backdrop matters as well: how inflation expectations evolve, how central banks communicate their policy paths, and how fiscal policy evolves to accommodate deficits while maintaining credibility in currency markets. The combination of these factors suggests that traders should emphasize risk-aware positioning, robust hedging, and ongoing reevaluation of the inflation regime as new data becomes available.

In sum, Permanent Inflation is not merely a slog of higher prices; it represents a shift in the long-run inflation regime that has material implications for asset pricing, risk management, and the behavior of households and businesses. It calls for a disciplined, data-driven approach and an adaptable strategy that can respond to evolving inflation dynamics, debt service burdens, and policy trajectories. As with all narratives in finance, the key lies in treating these dynamics as probabilistic rather than deterministic, maintaining flexibility in strategy, and using a robust framework to monitor ongoing shifts in inflation expectations and their real-world consequences.

Realized Gains, Losses, and the Banking System’s Asset Mix: A Closer Look

Understanding the health of the financial system requires looking beyond headline profitability and into the composition of assets and the realized gains and losses that banks report on their books. A notable focus is the prevalence of U.S. Treasuries on bank balance sheets. Treasuries are widely held due to their liquidity and perceived safety, particularly in uncertain times, but the concentration of these assets raises questions about risk concentration and interest-rate sensitivity. The realized gains and losses associated with these securities can materially affect a bank’s earnings profile, capital adequacy, and resilience in stress scenarios.

If banks are carrying large positions in Treasuries and rates move sharply, the mark-to-market losses could erode capital, influencing lending capacity and confidence in the banking sector. Conversely, gains on Treasuries can buoy balance sheets in the near term but may be reversed if yields rise and asset values fall. The broader implication is that the bank sector’s health is not solely a function of current earnings but also of exposure to rate shocks, liquidity conditions, and the potential for future mark-to-market fluctuations. The emphasis on Treasuries, therefore, signals that the asset mix matters for risk in ways that may not be immediately visible from standard profitability metrics.

The general relationship between the health of the economy and the condition of banks is well established: in strong economies with rising employment and incomes, banks typically benefit from stronger credit demand and lower default risk, which supports profitability and asset quality. During downturns, credit conditions can tighten, defaults may rise, and earnings pressure can intensify. The current juxtaposition—perceived economic strength in headlines alongside concerns raised by the banking sector’s asset mix—emphasizes the complexity of assessing financial stability in an inflationary, high-rate environment. It also highlights the need for ongoing vigilance about balance-sheet composition, liquidity risk, and the sensitivity of earnings to shifting macro conditions.

For investors and traders, the relationship between inflation, debt, and bank health is a critical knot to untangle. If inflation remains persistent and rate expectations stay elevated, banks’ net interest income can improve, but if credit demand weakens and defaults rise, profitability can deteriorate. The net effect depends on the balance between these opposing forces and the particular risk profile of each institution. The takeaway is that the durability of the financial system hinges on a delicate balance of asset quality, interest-rate risk management, and the ability of banks to maintain liquidity while supporting the broader economy. As conditions evolve, market participants should monitor the banks’ disclosures about interest-rate sensitivity, balance-sheet risk, and capital adequacy to gauge the true extent of resilience or vulnerability in the system.

The broader narrative remains that the health of the financial system is interwoven with macroeconomic policy, inflation expectations, and debt dynamics. A robust banking sector supports lending, investment, and growth, but these positive effects can be offset by financial stability risks if asset mixes become vulnerable to rate moves or if liquidity constraints tighten. The ongoing evaluation of the banking sector’s strength thus requires a careful synthesis of credit quality data, capital adequacy metrics, and liquidity indicators, alongside the macro signals for inflation and growth. Only by taking a holistic view can traders and policymakers assess the true trajectory of financial stability and the potential implications for markets.

Inflation, Real Purchasing Power, and Post-Pandemic Market Performance

A central question for traders after the seismic shifts of the pandemic era is how much of a real gain or loss has been achieved once inflation is accounted for. The period since the pandemic began has seen dramatic shifts in prices, policy responses, and market valuations. To gauge real performance, one can compare nominal portfolio values against a cumulative inflation measure. If inflation has averaged around a given rate over the period, the real return on investments can be significantly different from the nominal return indicated by price charts alone.

In practical terms, consider a hypothetical scenario: a one-million-dollar portfolio in March 2020 would need to rise to approximately $1,190,000 by the present to be at break-even in real terms, after adjusting for inflation. This calculation underscores the importance of considering inflation as a material drag on purchasing power, even when nominal gains appear substantial. The contrast with the S&P 500’s performance in the same interval highlights the complexity of market timing and asset selection. The index has risen by roughly 65 percent since March 2020, a substantial nominal gain. Yet the real value of gains depends on how inflation has eroded purchasing power over that period. It is not unusual for an index to deliver pronounced nominal appreciation while real gains lag behind or even turn negative when inflation is high and persistent.

Moreover, the market’s behavior during the pandemic—an era of economic lockdowns and unprecedented policy measures—created a paradoxical environment: investors could observe a rapid rebound and significant nominal appreciation, even as the broader economy faced substantial structural challenges. This divergence between nominal market performance and real purchasing power is a reminder that price movements do not automatically translate into commensurate improvements in living standards or long-run wealth, especially when inflation persists at elevated levels.

The broader implication for trading and portfolio strategy is clear: inflation-adjusted performance matters as much as nominal performance when assessing long-run wealth creation. Investors should place emphasis on assets with genuine pricing power, resilient cash flows, and hedging characteristics that help preserve value in inflationary environments. The persistent inflation regime also calls for careful consideration of asset-liability management, including the real-yield profile of fixed-income positions, inflation-linked instruments, and the potential benefits and costs of holding assets whose value is more resistant to inflationary erosion. In practice, this translates into building a diversified portfolio that can deliver real returns even when consumer prices are elevated, while maintaining the flexibility to adjust exposure as inflation expectations evolve.

The broader narrative emphasizes that, post-pandemic, many investors experienced substantial nominal gains, but the real picture depends on inflation-adjusted returns. As the inflation regime becomes a long-run feature of the economic landscape, strategies aimed at preserving purchasing power—and not merely chasing headline returns—are likely to prove more resilient. This perspective encourages a balanced approach that includes growth-oriented equities with sea-change capabilities, quality balance sheets, and defensive positions to weather inflation surprises. It also underscores the need for ongoing assessment of macroeconomic assumptions, the pace of rate adjustments, and the interplay between inflation, growth, and asset prices.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Trading: A Strategic Advantage

In markets characterized by rapid information flow, noisy headlines, and complex cross-currents of macro forces, artificial intelligence (AI) trading tools offer a potential edge for skilled traders. The core proposition of AI in trading is not magic but a disciplined, data-driven approach that learns from failures, remembers outcomes, and continually refines its models to identify patterns that human analysis might miss. The emphasis is on leveraging AI to capture the market’s pulse, interpret the deluge of daily headlines, and identify movements in price that reflect a confluence of underlying factors, from macro data releases to micro-structure liquidity shifts.

The practical utility of AI in trading rests on several pillars. First, AI can process vast datasets to identify correlations, sensitivities, and regime shifts that might escape manual analysis. Second, AI can contribute to risk management by designing and implementing dynamic hedging and position-sizing strategies that adapt to evolving market conditions. Third, AI-driven systems can complement human judgment by providing probabilistic scenario analyses and stress-testing across a wide range of market outcomes. The combination of quantitative rigor and adaptive learning capabilities enables traders to develop strategies that are more resilient to headline-driven noise and random fluctuations.

However, adopting AI in trading also raises important caveats. Markets are not fully deterministic systems, and AI models are only as good as their training data and underlying assumptions. Overfitting to historical episodes can generate brittle strategies that fail when conditions diverge from the past. Moreover, the deployment of AI in financial markets must manage model risk, data integrity, and the potential for unintended feedback effects—where the collective actions of AI-driven traders could amplify trends or exacerbate volatility during stressed episodes. Responsible use requires robust governance, ongoing validation, and a disciplined approach to risk controls and capital allocation.

For traders seeking to integrate AI into their toolkit, a pragmatic path involves combining AI-enabled insights with human oversight and domain expertise. This approach entails using AI to surface potential signals, quantify projected outcomes, and inform decision-making while maintaining explicit limits on downside risk and prioritizing capital preservation. In a regime marked by abnormal market dynamics and unpredictable outcomes, AI can function as a complementary mechanism that enhances cognitive capacity, speed, and diversification of viewpoints, rather than replacing the human element entirely.

The broader takeaway is that AI represents a powerful enhancement to trading discipline, not a substitute for sound judgment or risk management. It provides a way to navigate the complexity of modern markets by enriching analysis, expanding the set of tested scenarios, and enabling more precise execution. For traders, incorporating AI into a well-structured trading plan—one that emphasizes risk control, transparent performance metrics, and continuous learning—can be a meaningful step toward improving decision quality in an environment where traditional models are pushed to their limits by structural changes in inflation, debt, and policy.

Note: In keeping with best practices for publishing, this article omits promotional calls to action and extraneous marketing content. The emphasis remains on analysis, interpretation, and practical implications for readers seeking to understand abnormal market conditions and how to respond strategically.

Post-Pandemic Performance, Real Returns, and the Inflation-Adjusted View

Having assessed the indicators, debt dynamics, inflation prospects, and the AI trading angle, it’s essential to synthesize how the post-pandemic market actually performed when viewed through the lens of inflation-adjusted returns. The nominal gain in key equity indices since the onset of the pandemic has been substantial, with the S&P 500 recording significant upside. Yet the real wealth created for investors depends on the inflation backdrop during the same period.

To illustrate, if a portfolio stood at one million dollars in March 2020, the inflation-adjusted value today would require roughly $1.19 million to break even in real terms, assuming a cumulative inflation rate around -19 percent relative to a baseline. This adjustment translates the nominal performance into a real context, reminding readers that inflation can erode purchasing power even as nominal asset prices rise. The contrast between a 65 percent nominal rise in the S&P 500 from March 2020 and the inflation-adjusted break-even calculation highlights a critical point: the real value of gains depends on the inflation path experienced over the investment horizon.

The broader market takeaway is that real returns must be weighed alongside nominal returns. Investors who keep their eyes solely on dollar-denominated gains risk overstating the true wealth created. Inflation acts as a hidden tax on wealth, reducing the purchasing power of nominal gains and potentially altering the risk-reward calculus of hold-versus-sell decisions. In a world of elevated inflation expectations and persistent price pressure, strategies that value durable cash flows, inflation hedges, and risk management tend to perform more robustly over time than those that rely primarily on rising nominal prices.

From a portfolio-management perspective, this calls for a more nuanced approach to asset allocation. The emphasis shifts toward assets with revenue visibility, pricing power, and the ability to pass costs through to customers in inflationary environments. It also encourages the use of hedges and defensive positions to safeguard against inflation surprises and rate shocks. Additionally, investors should consider the implications of the debt dynamics and the policy backdrop for long-duration assets, as the combined effects of higher debt service costs and potential shifts in monetary policy can influence the relative attractiveness of different asset classes.

The post-pandemic performance narrative therefore centers on a broader truth: nominal gains matter, but they are incomplete without context. Inflation-adjusted returns provide a more accurate representation of real wealth creation and the sustainability of investment outcomes in a world where price levels drift higher, policy responses are complex, and debt burdens constrain fiscal maneuverability. The path forward calls for disciplined risk management, diversified exposures, and a willingness to adapt to evolving inflation expectations and policy signals.

The Trading Playbook in an Abnormal Regime: AI, Risk, and Adaptation

In the face of an abnormal regime shaped by permanent inflation, high debt, shifting monetary policy, and evolving risk dynamics, traders must craft a playbook that emphasizes adaptability, discipline, and the disciplined use of technology. The core idea is straightforward: align trading decisions with the most robust cross-cutting signals, minimize unhedged risk, and continuously validate assumptions against fresh data. In practice, this means a blend of quantitative analysis, scenario planning, and prudent risk controls that adapt as conditions change.

Key components of an effective playbook in this environment include:

- A multi-signal framework: Combine valuation indicators, macro momentum, policy expectations, inflation indicators, and market breadth data to avoid overreliance on any single metric. This reduces susceptibility to regime-specific distortions and helps identify genuine regime shifts.

- Dynamic risk management: Implement position-sizing rules, stop-loss protocols, and hedging strategies that respond to changes in volatility, liquidity, and correlation patterns. In abnormal markets, risk controls are a trader’s primary line of defense against drawdowns and liquidity squeezes.

- Inflation-aware asset selection: Favor assets with pricing power and stable cash flows, while incorporating inflation-linked exposures and hedges that can preserve purchasing power in rising-price environments. Evaluate sectors and companies on their ability to maintain margins when input costs and financing costs rise.

- Liquidity-conscious execution: In markets that can swing on headlines and policy signaling, execution quality becomes crucial. Trade planning should optimize for liquidity, minimize market impact, and consider the timing of trades to ride favorable flows.

- Continuous learning and feedback: Adopt an AI-assisted framework for backtesting and live-learning while maintaining a human-in-the-loop approach to avoid overfitting and to ensure interpretability of model outputs.

Crucially, the trading playbook must remain flexible. The abnormal regime is characterized by shifting relationships between macro variables, assets, and policy measures. A rigid strategy can become a liability as conditions evolve. The most resilient traders are those who can recalibrate strategies in light of new information, reassess risk budgets, and adjust exposure to reflect the changing probability distribution of outcomes.

Finally, readers should recognize that all trading involves risk, especially in volatile, inflation-driven markets. Risk capital should be used, and proper disclaimers and compliance practices should be observed in all trading activities. The crux of the approach is to combine rigorous analysis with a disciplined execution framework, ensuring that decisions are grounded in data and aligned with a coherent risk management plan. The ultimate goal is to improve the probability of favorable outcomes while preserving capital in the face of an uncertain and rapidly changing macro-financial environment.

Conclusion

In a period marked by pronounced deviations from historical norms, investors and traders confront a landscape where normal is no longer a reliable anchor. The Warren Buffett Indicator, historically a barometer of valuation relative to GDP, signals that valuations are significantly elevated in today’s regime, suggesting overvaluation and heightened bubble risk. The macro backdrop — with a dramatic shift from a near-zero federal funds rate in 2021 to a policy stance around 5.33 percent in 2024 — challenges conventional wisdom about the rate-valuation relationship and underscores how inflation expectations, debt dynamics, and policy signals intersect to shape price discovery.

The rapid rise of interest payments on the national debt, surpassing top budget items and pointing toward a sustained financing burden, reveals a structural challenge for fiscal policy and market stability. This, combined with the heavy Treasuries exposure on bank balance sheets and the specter of higher debt-service costs, highlights the fragility that can emerge in an inflationary environment despite seemingly strong macro headlines. The prospect of policies like taxation of unrealized gains, while politically debated, illustrates the kinds of nontraditional tools that policymakers might consider in a bid to shore up finances—tools that could have profound implications for market liquidity and asset pricing.

In this context, Permanent Inflation emerges as a central theme, reshaping expectations for purchasing power, the real value of returns, and the long-run configuration of risk premia. It invites a reorientation of investment strategies toward assets with durable pricing power, inflation hedges, and high-quality earnings that can weather higher financing costs. It also accentuates the importance of advanced analytical tools, including AI-driven insights, that can synthesize large data streams and provide decision-support in a landscape where headlines move markets rapidly and the true drivers of price action are often diffuse and complex.

For traders, the takeaway is not to fear abnormal conditions but to adapt with discipline. The market’s direction—whether up, down, or sideways—depends on a careful balance of risk controls, valuation judgment, macro awareness, and the ability to learn from ongoing feedback. In an era defined by structural shifts to inflation, debt sustainability, and policy signaling, the most successful participants will be those who cultivate a robust framework for analysis, diversify their exposures, and maintain a flexible approach to strategy and execution. The ultimate test is not merely predicting price movements but evolving in step with the changing anatomy of risk, so that timing, capital preservation, and strategic positioning align with a world where the normal is forever evolving.